Archiving as Presentation

The modern world is caught up in a kind of perpetual war between memory and forgetfulness. In this session, speakers and attendees will engage in a conversation about how they negotiate this tension through archival practices and methodologies that approach the archive as more than just a static repository of past productions. Speakers and attendees will share their perspectives and practices concerning the technological and ethical challenges of building and authoring an archive; the possibilities of sharing archival resources and findings across diverse organizations and publics; and the ways that an archive can extend a program beyond the original time and space of the project.

Session led by Aaron Levy, Slought Foundation; Lauren Cornell, Rhizome; and George Scheer, Elsewhere.

Introduction

“Archives aren’t things we push into storerooms, they’re active bodies of knowledge, especially with so many of the organizations here coming up on their thirtieth or fortieth anniversaries,” remarked Lauren Cornell, who welcomed the audience and then gave the floor to Aaron Levy.

Slought Foundation

Levy led off with a description of the work of the Slought Foundation, which produces dialogs about cultural and social change. Ten years worth of dialogs—more than 600 hours of audio recording—are available free through their website. In the past few years the Foundation has begun to work with the archives of artists such as Ai Wei Wei and John Cage, and conducted interviews with all the living directors of the Venice Biennale for Architecture, which were published by the Architectural Association London.

“We don’t just store things,” said Levy, “We look for other models that can be mobilized in the service of our practice. The John Cage Foundation approached us about making a permanent sound installation in of Cage’s 1989 performance How to get started. But to be true to what that artist was about we had to think more broadly than just installing the work. Cage, who was at a sound design conference at the Skywalker Ranch in Nicasio, extemporized about things that were important to him: music, Duchamp, mushrooms. The installation includes both a sound installation and a recording console. You can listen to Cage’s performance, listen to what the visitors before you recorded, and record your own version of the piece. We’re thinking of the archive as something very personal that will include what is meaningful to the people that pass through the room. It’s a co-constructed archive.”

Elsewhere

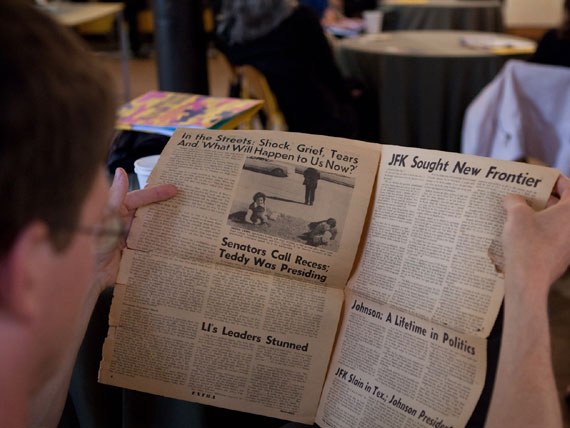

As his introduction, George Scheer held up a tattered, yellowed Newsday with two-inch headlines screaming “Extra! Assassin Kills JFK in Dallas.” He passed it around saying, “My grandmother, who ran a store from 1939 to 1997, amassed a huge inventory, filling three floors of her house with items. It doesn’t matter if you handle it, or even take it.”

“That’s the starting point for Elsewhere, a position between archiving catastrophe and unfolding artwork. We invite artists in to work with the stuff, create their own archival process. Their mark is the work of categorizing; it’s a practice of arrangement, organizing and reorganizing works that continue to be available for continued transformation. My grandmother had wrapped things in plastic bags with knots and ties; I think of the packages a puzzle pieces and the house as a box of puzzle pieces. They can be arranged and rearranged—artists create works knowing that they may be part of other works in the future. It’s a layered process not unlike the Cage piece that Aaron just described. With an unfolding artwork, the questions become how do you portray that history going forward and how can you make the work legible over time. The residency program validates the practice of artists who leave their mark on the collection, which will be discovered by other visitors to Elsewhere.”

Rhizome

“I’m going to focus on our online archive of digital art,” said Lauren Cornell. “The process feels more boring that what you two are doing…we’re not problematizing the process, we’re trying to create a comprehensive, useful collection of digital work. Rhizome is a nonprofit website founded by Mark Tribe, an artist who is now on our Board, in 1996. We’re 15 years old, which is very old in Web time—Netscape and AOL old. It becomes a question of keeping the website relevant. You can wipe a gallery clean, but not a website; we have 15 years of art information we’re trying to activate and reconsider constantly.

“Rhizome was one of THE organizations to support Internet art, and in 1999 Tribe added an open, grassroots repository called ArtBase. People would chuck in links—there are all kinds of projects, software, code, websites, games. In 2005, when I took over, we began working to make our archive something that could support us in our future, a resource that students and teachers could use. If I’d had six Google programmers we could have done it in two months but we didn’t so it’s taking longer.

We’re reaching out to the 2500 artists who have works in the archive, figuring out how work that was made in formats that are no longer around can be made available, and making digital copies. I worked at Electronic Arts Intermix before I started at Rhizome and I think of them as a model. Howard Wise started Intermix; people left tapes at his house and he had to figure out how to turn them into an archive.

“The archive is still growing. Artists upload their works to our site—we have over 5000 portfolios. When they upload the work is automatically submitted to Rhizome staff for consideration, and if we select, it we work with them to make a copy and figure out standards compliant metadata. Artists can write their entries and annotate but our staff is monitoring and editing. We also do a lot of online exhibitions and participatory projects. At the same time we’re creating a collection, we’re sustaining and historicizing it collectively, writing a history of this field.”

Audience The moment archives move into a digital realm they are extremely mediated. There’s a loss of virginity, the work already categorized, but digitization also allows you to find files and relate work that would probably never have been related before. What do find are the most fascinating opportunities for digital archives?

Cornell People spend a lot of time talking about social media, but what really drives the Web is good content. So we’ve emphasized publishing and contextualizing work. We look for interesting questions, such as how does this early internet art compare to early video art?

Levy We don’t approach the archive as a static past. We want to hone and refine it, make the archive a site of contemporary production.

Cornell Perhaps there’s an opportunity to collaborate between all our organizations right now. It would be good if we could cross-reference instead of creating isolated silos.

Audience Would standards compliant metadata do that?

Audience Has that already been developed by somebody?

Cornell We didn’t develop our own. We chose different metadata schemes that we thought we could bet on…ARTstor, Getty.

Levy Don’t you want things to get lost in the archives?

Cornell I think we’re on different ends of this!

Scheer For us it’s about an encounter, it’s what you find along the way when you think you’re looking for something else. An object can be viewed from multiple vantage points over time and we want to be surprised, to keep pulling things out of the box.

Audience Browsing is not hard to do. If there is consistent metadata you can ignore it. Categories are great for researching things in a systematic way but even online archives usually have a browse feature that lets you wander around.

Cornell Obviously Aaron and I are coming at this from different angles. It’s not in our mission to lose artists’ work. [laughter]

Audience At Exit Art, we had a show about alternative spaces in New York starting in the 1960s. The crux of exhibition was a collection of boxes filled with elements from all of these spaces. People would sit there for hours looking through the boxes. We’re planning to make a book…

Scheer One of the challenges is the process of documentation. Art practices are often chaotic and ideas are grabbed from all over the place.

Audience I want to play devil’s advocate, to say that archiving has become an “ism” like minimalism. It’s a form of practice that has been privileged by October Magazine—an artist like Tacita Dean makes the grade. It seems like this academic high ground that’s been built up around the archive is rooted in recent history. I would date the starting point to Katherine David’s 1997 Retro Perspectives, which reintroduced artists such as Helio Oiticica and looked at them through the lens of contemporary art. Since then archiving has been taught as curatorial model, eclipsing other possibilities of art practice. I’m a little suspicious of endeavors constructed by intellectuals and art historians who are disappointed in present. Perhaps as the current generation began to analyze history of their teachers in last decade archiving and archivalism have gotten out of control.

Audience There is a vein of fear that there might be an “ism” but what is fascinating is to realize the non-neutrality of archives, that there is ideological content every time you label something. It might be important in the future to know when something was archived, to know for example that a poster from 1962 was cataloged in 1999.

Audience Roberta Smith called this “no artist left behind,” which I think was a succinct analysis of the problem. Maybe we don’t need to see all this stuff again…maybe some things had value in their time and its time to move on. She had the exasperation of critic who looks at new things all the time.

Levy I think there’s an anxiety about the present and memory that has led to regarding the archives as memory. Creating an archive is powerful when it enables models to be recovered that inform a different way of thinking about contemporary practice. For me there’s something politically emancipatory about the construction of an alternative archive.

Audience It’s also a way to commoditize artists’ legacies, specifically performance artists and choreographers who begin thinking of their archive when they’re asked about its purchase. There aren’t works someone can add to their collection but they can acquire 38 boxes of related materials.

Audience It’s about how it becomes interactive…I can curate my life differently through access to history. There are comparisons that open new fields for the present and future because there’s a symbiosis and a connection there…what we’re recording changes the way we look forward.

Audience There are those who claim that Youtube has destroyed popular music, that access to the past has destroyed the present. I think it’s a valid argument. There’s no innovative new music made that isn’t wholly reflective of some past form.

Audience I have work on Rhizome. I never thought of it as an archive but as an exhibit.

Levy The other way to think of the archive is the economic. We spend lots of time and energy but it’s a very inexpensive means to engage a constituency.

Audience The argument that access to the box will erase new content is problematic. The spirit of every time is to be able to position itself in relation to its context.

Cornell The goal for us in creating this collection is to understand the history so we don’t repeat it going forward. I see so many artists doing the same things that Nam June Paik, did having the same conversations that people did in Radical Software.

Audience Is he saying that innovation in the past was founded on ignorance?

Audience The fundamental desire of modernism was to kill your parents…today we are acquainted with the entire family tree.

Audience As we all create the archives of our organizations perhaps we should have an initiative to coordinate, to look for the artists that link our collections and so forth.

Cornell It’s time to stop. Thank you, everyone.

Postscript

As the audience filed out, Scheer was approached by a woman who asked if it was truly okay to keep the Newsday. Scheer kept his word.